“Woke” Intolerance At Stanford Law School

May 6th, 2023 | By Dr. Jim Eckman | Category: Culture & Wordview, Featured IssuesThe mission of Issues in Perspective is to provide thoughtful, historical and biblically-centered perspectives on current ethical and cultural issues.

We have all heard the term “woke.” It is part of our cultural dialogue. With an obvious difference in emphasis, both the left and the right along the political spectrum use the term. But, what exactly does “woke” mean in American civilization? Ross Douthat has perhaps given the best summary of the power and appeal of “wokeness.” All Americans treasure equality and liberty; we seek to transform these ideals into living reality within our culture. But there remain limits, disappointments and defeats—and terrible disparities persist. Therefore, for the left, there are “cultural and psychological structures that perpetuate oppression before law and policy begins to play a part . . . the way that generations of racist, homophobic, sexist, and heteronormative power have inscribed upon themselves, not just on our laws but our very psyches. And once you see these forces in operation, you can’t unsee them—you are, well, ‘awake’—and you can’t accept any analysis that doesn’t acknowledge how they perpetuate our lives. This means rejecting, first, any argument about group differences that emphasizes any force besides racism or sexism or other systems of oppression.” “Wokeness” also means “rejecting or modifying rules of liberal proceduralism, because under conditions of deep oppression those supposed liberties are inherently oppressive themselves . . . You can’t have real freedom of speech unless you first silence oppressors . . . schools, media, pop culture and language are the essential battlegrounds.”

Columnist Bret Stephens argues that wokeness seeks “to tear things down, divide Americans, reject and replace our national foundations.” Stephens sees four essential characteristics of this “ideology-cum-protest” movement:

- An allegation that racism is a defining feature, not a flaw, of nearly every aspect of American life, from its inception to its present, in the books we read, the language we speak, the heroes we venerate, etc.

- Its prescription is not for genuine dialogue and debate but indoctrination and “extirpation.” Indeed, America’s past is shot through with racism. “But the allegation is also incomplete, distorted, ungenerous to former generations that advanced America’s promise, and untrue to the country most Americans know today.”

- Wokeness operates as if there had been no civil rights movement and that white Americans hadn’t been an integral part of it. It operates as if 60 years of affirmative action never happened, and that an ever-growing percentage of Black Americans don’t belong to the middle and upper class . . . It operates as if we didn’t elect a Black president and bury a Black general as an American icon.”

- Wokeness prescribes solutions that are more Orwellian than anything else. “It’s a blunt attempt to turn everyday speech into a perpetual, politicized and nearly unconscious indictment of the ‘system.’ Anyone who has spent time analyzing totalitarian regimes of the 20th century will note the similarities.” It involves an element of government coercion.

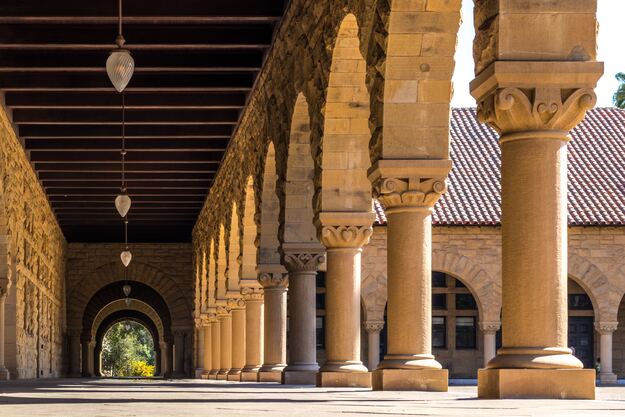

A perfect example of the Orwellian nature of wokeness is Stanford University Law School. Gerard Baker of the Wall Street Journal reports that “Ninety-seven percent of the nation’s top 100 law firms employ Stanford alums as partners; 92 have Stanford alums as attorneys. For 48 consecutive years Stanford graduates have clerked on the Supreme Court. Microsoft, Google, Cisco and many other top firms have employed a graduate as general counsel.” He then poses these poignant rhetorical questions to these law firms and corporations: “Do you stand with Jenny Martinez or do you cower behind Tirien Steinbach? Do you want your institutions to be places where the law is respected as the authority that mediates our disputes is blindfolded or are you going to continue to connive at the transformation of the law into a tool of the new identity-class struggle? Are you going to keep facilitating the degradation of the most basic of our freedoms—speech—or will you begin the long struggle against the controlling zeitgeist of totalitarianism?”

What is Baker talking about? Judge Stuart Kyle Duncan, a Columbia Law School graduate who serves on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit, was invited by Stanford Law School’s Federalist Society chapter to talk about his court “in conversation with the Supreme Court.” Some progressive students especially disliked some of his views concerning social issues—same-sex marriages, transgender rights, abortion, pronouns, etc. After anti-Duncan posters were placed around campus, Tirien Steinbach, Stanford’s associate dean for DEI [Diversity, Equity, Inclusions] officer, in an email, associated herself with Duncan’s critics, but said protests must comply with Stanford’s policy against disrupting speakers.

After being introduced by the Federalist Society’s president, a gay man, Duncan tried to speak into a din of shouting: “You’re not welcome here, we hate you,” “You have no right to speak here,” etc. After about 10 minutes, Duncan responded angrily to the hecklers and asked for help from the Stanford administrators present, “sitting like potted plants amid the chaos.” Steinbach went to the lectern and read a statement obviously written in anticipation of this opportunity to pander to the inflamed progressives: She was “pained” that Duncan was welcomed at the school because his previous work and words had caused “harm” to students, including the “absolute disenfranchisement of their rights.” She blamed him for inflaming the protesters by responding to them. She was “deeply, deeply uncomfortable” because the Federalist Society’s event was “tearing at the fabric of this community.” Continuing with her self-absorbed inventory of her feelings, and “fluent in DEI-speak,” she told of her labors creating “a space of belonging” and “places of safety.” She said, with Duncan standing nearby, that even “abhorrent” speech that “literally denies the humanity of people” should not be censored “because me and many people in this administration do absolutely believe in free speech.”

George Will writes that “The “many”—implied: not all—Stanford administrators who believe in free speech (as much as Steinbach does) do not believe so fervently that they enabled him to deliver his prepared remarks. During a brief, tumultuous question period he was called ‘scum,’ and afterward Steinbach reportedly said the protesters had not violated Stanford’s non-disruption policy and that Duncan had been disrespectful to the audience because he did not continue reading his prepared remarks through the howling gale of insults.” Stanford’s president and the law school’s dean jointly say “they are sorry about the unpleasantness. Not, however, so sorry, as of this writing, that they have fired Steinbach—although they say she refused to do her job: ‘Staff members who should have enforced university policies failed to do so, and instead intervened in inappropriate ways that are not aligned with the university’s commitment to free speech.’ The depth of that commitment can be gauged by this tepid rebuke, in bureaucracy-speak, of Steinbach for being improperly ‘aligned.’ As this is written, many of Stanford’s future lawyers are demanding that the dean apologize for apologizing. Stanford has not expelled any of the imperfectly ‘aligned’ disruptors. The school might be improved by the departure of the student whose idea of intellect in the service of social justice was to shout sexual boastings and scabrous insults.” Correctly, Ilyn Shapiro, Director of Constitutional Studies at the Manhattan Institute, argues that the only solution to the mess that Stanford represents is to purge “DEI bureaucrats that undermine the liberal values of academic speech and due process.”

One final thought about what the Stanford mess teaches us: Americans divide their social world into types or groups that are essentially different; indeed, that some groups are actually superior to others. Necessarily then, the boundaries between groups are clear, hard and “anybody adopting the culture of another group is guilty” of betrayal against their own “group.” Columnist David Brooks writes that there are at least two “large social movements in American life on different spots” of the cultural spectrum. On the right, there is “the ethnonationalist, white nationalist position that race is real and it will always be there, and societies will thrive insofar as the supposedly superior group manages to stay in charge.” On the left, there is the tendency that holds “that race is so essential and so deeply baked in that it will always define communities and societies, and rather than having a liberal democracy in which we primarily are seen as individual citizens with the same rights and duties, we should primarily be seen as members of our racial or religious communities.” Russell Moore, editor of Christianity Today, wisely concludes that one of the results of this tribalism or putting people into rigid silos is seen in politics: “In our world, politics is no longer about philosophies of government but about identity . . . And in such a world, nationality and politics, even in their smallest trivialities, seem far more real than the kingdom-of-God realities that Jesus described in terms of a seed underground or yeast working through bread or wind blowing through leaves.” Hence, we often “use” Christianity to get us to some other goal.

The church of Jesus Christ should therefore model the supernatural impartiality that refuses to discriminate on the basis of race or ethnic origin. The church has no need for a director of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion. The church should model reconciliation of all races and ethnic groups. The church should cut the radical path for all of society, for it alone sees people the way God sees them: All bear His image and all need Jesus Christ. The church has the radical solution to society’s struggle with racism, prejudice and discrimination: Disciples of Jesus Christ love one another with the supernatural love of their Savior. The church is the living example of racial unity and harmony, welcoming and including people from all racial and ethnic backgrounds to full and equal fellowship in the body of Christ.

See Ross Douthat in the New York Times (19 March 2023); David Brooks in the New York Times (8 October 2021); Russell Moore in Christianity Today (November 2021), p. 34; Bret Stephens in the New York Times (10 November 2021); Gerard Baker in the Wall Street Journal (28 March 2023); David Leonhardt, “The Morning” in the New York Times (24 March 2023); George F. Will, “Expensively credentialed, negligibly educated Stanford brats threw a tantrum” in the Washington Post (15 March 2023); and Tunku Varadarajan interview with Shapiro in the Wall Street Journal (1-2 April 2023).