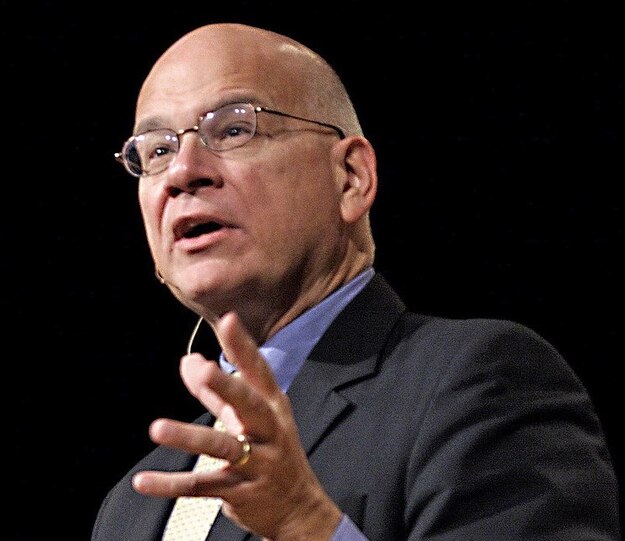

Remembering Tim Keller

Jul 1st, 2023 | By Dr. Jim Eckman | Category: Featured Issues, Politics & Current EventsThe mission of Issues in Perspective is to provide thoughtful, historical and biblically-centered perspectives on current ethical and cultural issues.

Credit: Frank Licorice – https://www.flickr.com/photos/118175464@N04/13893171622/ – CC BY-SA 2.0

Tim Keller, pastor of Redeemer Presbyterian Church in Manhattan (a church he planted with his wife Kathy in 1989), died of pancreatic cancer on Friday, 19 May 2023; he was 72 years old. In less than a decade after he planted the church, 2,000 people were attending Redeemer; by the mid-2000s, attendance had increased to 5,000. The congregation was diverse, young, and cosmopolitan. Keller did not fit the norm as a pastor. Who would ever seek to plant a church in Manhattan? Yet, God blessed his ministry in remarkable ways. Peter Wehner, a senior fellow at the Trinity Forum, writes that “One of the things that made Tim distinct was his ability to bring an ancient faith into the modern city, into the lives of busy young professionals who might otherwise have dismissed it, and to do so with quiet confidence and not hostile defensiveness. He made the discussion of faith seem relevant, and exciting.” He was one of my spiritual heroes. He had a profound impact on my life for several reasons:

- I first became acquainted with Tim Keller through his 2008 book, The Reason for God: Belief in an Age of Skepticism, one of the best books to reach the unbeliever I have ever read. I then read the book he and his wife wrote on marriage, his book on prayer and then his most recent book on Forgiveness. Keller had a deep understanding of theology and Scripture but was able to communicate the authority of God’s Word to this lost and confused generation. He had the uncanny ability to quote C.S. Lewis, current cultural icons and mix them with verses from God’s Word. His messages and his books were masterpieces of contextualization. He knew how to reach people where they were in their lives. Perhaps that is the reason he successfully ministered in lower Manhattan.

- Keller read widely and knew how to work history, cultural analysis and science into a holistic presentation of a biblical apologetic. Peter Wehner observes, speaking of a Jewish friend who engaged with Keller in lengthy discussions, that “What always stood out most to me in talking to Tim was the pleasure he took in sharing his deep knowledge of scripture and theology . . . It was like he was sharing a gift, something he had that he knew his friend would love. We unavoidably spoke across the line that separates Christians from Jews, and yet Tim approached that line like a low fence between friendly neighbors, the kind of fence you’d stand at for hours to chat about what matters most in life, not a high wall that divides.” Over time, some in the Christian world came to criticize Tim’s commitment to this sort of engagement as a weakness, or at least, as an approach poorly suited to this moment. “I would argue quite the opposite,” Bill Fullilove, the executive pastor at McLean Presbyterian, told me. “His model of gracious and thoughtful engagement, even when disagreeing vehemently, is exactly what we need more of today. It is simply impermissible to pursue biblical goals while ignoring biblical ethics. And what Tim did was marry the best of intellect and argument and eloquence with a truly gracious and kind and biblical spirit, both in person and in a large room.” I learned much from him in this area.

- His irenic spirit was compelling. Keller stood firm in his beliefs and convictions sourced in Scripture. Yet he did not shred his opponents, which were many, nor did he consider them evil beings who needed to be destroyed. He saw each person as of infinite value to God and therefore to him. He treated atheists, opponents and his enemies with grace and compassion. Russel Moore illustrates my point: “Over the past several years, Tim and I were often in conversation with unbelievers—some curious and irenic about faith, others dismissive and hostile. I remember stifling laughter when an atheist whom Tim loved and respected told a group of us that the need for transcendence could now be met with psychedelic mushrooms. I watched Tim’s eyebrow go up . . . Watch this,I said to myself. In every one of those interactions, I never once saw Tim humiliate someone with arguments, even though he could easily have done so. ‘Well, let’s think about this for a minute,’ he said to the atheist arguing that morality could be explained by evolutionary process alone. Tim explored this man’s objections to human slavery, imagining them in the context of a cosmos without any transcendent moral order. In so doing, he affirmed the rightness of the man’s moral intuitions while simultaneously showing how his theory couldn’t bear the weight of those same intuitions. Once again, he showed where the mind and the soul (or the mind and the conscience) were at odds and pointed to a better way. At the end of the conversation, there was no question that Tim understood the argument and had responded with devastating clarity. But we also knew that his talk wouldn’t end up as a YouTube video titled ‘Watch Tim Keller Own the Atheist.’ He really loved the man and engaged him without passive retreat or intellectual intimidation. When I invited Tim to guest-speak in the Institute of Politics class I taught at the University of Chicago, most of the students were disconnected from people of faith and didn’t know who he was. David Axelrod, the director of the program at the time, said, ‘These kids have highly tuned B.S. detectors, and it’s almost like you could hear the shields coming down three minutes after he started talking.’ Many of them realized, Wait, this pastor is as smart as or even smarter than we are, and he’s not the least bit embarrassed about Christian orthodoxy and biblical authority.”

- His priority was the Gospel. As David Brooks comments, “He didn’t fight a culture war against that Manhattan world. His focus was not on politics but on ‘our own disordered hearts, wracked by inordinate desires for things that control us, that lead us to feel superior and exclude those without them, that fail to satisfy us eve when we get them. He offered a radically different way. He pointed people to Jesus, and through Jesus’ example to a life of self-sacrificial service.” He eschewed political debates and stayed away for politics. He believed that the church should stay above the raw, mean, ruthless political culture so prevalent today. He believed that pastoral leaders harm their congregations by bringing politics into the pulpit. He did not believe that spiritual leaders should bring politicians into their sermons nor into their pulpits. In 2017 he wrote: “While believers can register under a party affiliation and be active in politics, they should not identify the Christian church or faith with a political party.” He argued that the church should never devolve into “one more voting bloc aiming for power.” He believed the Christian serves King Jesus, not a political icon. Such convictions have influenced me personally in a significant way.

Collin Hansen, vice president of content and editor in chief of The Gospel Coalition, recently published Timothy Keller: His Spiritual and Intellectual Formation. I just finished reading this important book, which has personally helped me to understand the development of Keller’s thought and ministry. Here is a summary of salient aspects from Hansen’s book:

- “But that was Keller’s gift. It’s no cliché—he never stopped learning or growing. In my book, Timothy Keller: His Spiritual and Intellectual Formation, I describe his intellectual and spiritual development as rings on a tree. Keller retained the gospel core he learned from mid-century British evangelicals such as J. I. Packer, Martyn Lloyd-Jones, and John Stott. He grew to incorporate such varied writers as Charles Taylor, Herman Bavinck, N. T. Wright, and Alasdair MacIntyre. And he somehow synthesized them with Kuyper, Warfield, Newbigin, and dozens more in the middle.”

- “As many American Christians began to shift their social and political tactics in 2016, Keller came under increased criticism and scrutiny from fellow evangelicals. But anyone who followed his work over the decades could see that he was not the one who had changed. Keller did not court such opposition. Anyone working with him could attest to his extreme aversion to conflict. In all our personal conversations, I cannot recall hearing a single critical comment from him directed toward a fellow believer. His steadiness under this growing hostility gave courage and comfort to younger leaders who became disillusioned by the fall of so many of our former heroes.”

- “Even when Keller chastised evangelicals, he spoke and wrote as a pastor with love for his flock. Keller’s only mentor, Edmund Clowney, helped him to love the local church, warts and all. As easily as Keller quoted obscure academics or New York Times columnists, he aimed to build up the local church. And in the explosive early growth of Redeemer church, and again in the dark days after 9/11, Keller witnessed the Spirit moving in unexpected and powerful ways . . . Keller left American evangelicals with a vision for Christian community that disrupts the social categories of our culture. These thriving communities lend credibility to the transformative power of the gospel. Keller cited the work of Larry Hurtado in Destroyer of the gods: Early Christian Distinctiveness in the Roman World. In this incisive study, Hurtado showed how the persecuted early church wasn’t just offensive to Jews and Greeks. It was also attractive. The first Christians opposed abortion and infanticide by adopting children. They did not retaliate but instead forgave. They cared for the poor and marginalized. Their strict sexual ethic protected and empowered women and children. Christianity brought together hostile nations and ethnic groups. Jesus broke apart the connection between religion and ethnicity when he revealed a God for every tribe, tongue, and nation. Allegiance to Jesus trumped geography, nationality, and ethnicity in the church. As a result, Christians gained perspective so they could critique any culture. And they learned to listen to the critiques from fellow Christians embedded in different cultures.”

Finally, a word about how Keller faced the imminence of his death from pancreatic cancer. He wrote: “This is a dark world. There are many ways to keep that darkness at bay, but we cannot do it forever. Eventually the lights of our lives—love, health, home, work—will begin to go out. And when that happens, we will need something more than our understanding, competence, and power can give us.” He wrote those words in his 2013 book, Walking With God Through Pain and Suffering. Seven years later, in June 2020, he was diagnosed with Stage 4 pancreatic cancer. He knew then that it wouldn’t be long before the lights of his life would go out. “Despite my rational, conscious acknowledgment that I would die someday, the shattering reality of a fatal diagnosis provoked a remarkably strong psychological denial of mortality,” he wrote. “When I got my cancer diagnosis, I had to look not only at my professed beliefs, which align with historical Protestant orthodoxy, but also at my actual understanding of God.” Wehner writers that “Tim’s actual understanding of God proved to be more than enough to sustain him. He wanted to be cured, of course, and he knew that his last days were likely to be very difficult, and they were. But Tim was able to say that he was never happier, never had more days of comfort, and that his relationship with God had never been better. It was an extraordinary testimony. Tim was also transparent, admitting that he and Kathy—his best friend, his soulmate, the co-author of his life—would often cry together. It was impossible for them to imagine life apart from each other.”

David Brooks tenderly describes Keller’s last days: “Tim was confident, cheerful and at peace as he spiraled down toward death and upward toward his maker. His passing has made us all very sad, but if you go back and listen to his sermons, which you should, you come back to gratitude for his life and to the old questions: Death, where is your victory? Where is your sting?” Tim Keller is now enjoying the presence of His Lord and Savior. I am thankful to God for sharing him with us for 72 years. May He raise up more Tim Keller’s to engage this dark world with the Gospel.

See Collin Hansen “Tim Keller Practiced the Grace He Preached” www.christianitytoday.com (25 May 2023); Russell Moore, “Moore to the Point” (25 May 2023); Tish Harrison Warren in nytdirect@nytimes.com (28 May 2023); Peter Wehner, “My Friend, Tim Keller” in www.theatlantic.com (21 May 2023); and David Brooks in the New York Times (23 May 2023).