The Definition Of Citizenship: A Legitimate Controversy In 2018?

Nov 10th, 2018 | By Dr. Jim Eckman | Category: Featured Issues, Politics & Current Events

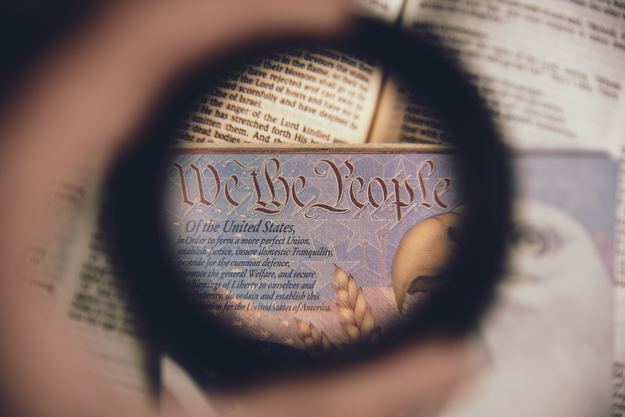

What is a citizen? When the Founders of this Republic wrote the Constitution during the summer of 1787, they did not include a definition of citizenship in the Constitution. During the early decades of the history of the American Republic, various laws were passed that heightened the ambiguity of what does citizenship mean and what are the requirements for citizenship? In the infamous 1857 Dred Scott decision, the Supreme Court was asked a constitutional question: “Can a negro whose ancestors were imported into this country and sold as slaves become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States, and as such become entitled to all the rights, and privileges, and immunities, guaranteed by that instrument to the citizen?” The Court ruled no on this question; slaves are property, not citizens. Furthermore, the Court argued, the Constitution barred Congress and the states from granting citizenship to the descendants of slaves. Thus, a black American could never be considered a citizen of the US with all the rights and privileges that go with citizenship. In 1857 this included all free blacks, some of whom had been freed as slaves and some who had never been a slave. Over 4 million Americans whose skin was dark were affected by this horrific decision. Because they were black they could never be a US citizen, whether they had been a slave or not. The Civil War (1861-1865) raised even more fundamental questions about citizenship. With the North victorious and with the 13th Amendment which abolished slavery in place, Congress had to deal with the ambiguity of citizenship in the Republic. The 1866 Civil Rights Act defined citizenship as “All persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign powers . . . are hereby declared citizens of the United States.” As the federal government had now defined citizenship, it was now up to that government to protect the rights of the now freed 4 million African-Americans. Therefore, in 1868 the 14th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified and adopted, declaring that anyone born on US soil was a citizen, with all the rights and privileges that go with it: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.” [This is the common law doctrine of jus soli, or rights of the soil.] The term “jurisdiction” has been clearly understood as referring to the territory where the force of law applies, and that means it applies to nearly everyone on US soil. In 1868, the only exceptions were diplomats (who have sovereign immunity) and Native Americans on tribal lands. The 14th Amendment therefore meant that the over 4 million African-Americans who had been slaves were now full-fledged citizens with all the rights and privileges that accompanied that status. The obnoxious reign of the 1857 Dred Scott was finally over!

Has the 14th Amendment’s “birthright citizenship” been upheld since 1868? Incontrovertibly yes. Consider the evidence:

- In the congressional debates over the 14th Amendment in 1866, Senator Edgar Cowan of Pennsylvania asked the Senate rhetorically, “Is the child of the Chinese immigrant in California a citizen?” Senator John Conness of California answered, yes. He went on, “The children of all parentage whatever, born in California, should be regarded and treated as citizens of the United States, entitled to equal civil rights with other citizens.”

- In 1898 the Supreme Court confirmed this understanding in the United States v. Wong Kim Ark, ruling that a child born in San Francisco to Chinese parents was a US citizen, even though the parents were prohibited by the Chinese Exclusion Act from ever becoming citizens. The Court ruled that “the 14th Amendment affirms the ancient and fundamental rule of citizenship by birth within the territory, in the allegiance and protection of the country, including all children here born of resident aliens . . .To hold that the 14th Amendment of the Constitution excludes from citizenship, born in the United States, of citizens or subjects of other countries, would be to deny citizenship to thousands of persons of English, Scotch, Irish, German, or other European parentage who have always been considered and treated as citizens of the United States.”

- In 1892, in Pyler v. Doe, the Supreme Court ruled that undocumented children were entitled to free public education. In doing so, the Court ruled on the basis of the “equal protection” clause in the 14th All 9 justices agreed that the “Equal Protection Clause protects legal and illegal aliens alike. And all nine reached that conclusion precisely because illegal aliens are ‘subject to the jurisdiction’ of the US, no less that legal aliens and US citizens.”

- John Yoo, who served in the George W. Bush administration and is now law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, argues that “the 14th Amendment settled the question of birthright citizenship. Conservatives should not be the ones seeking a new law or even a constitutional amendment to reverse centuries of American tradition.”

- Josh Blackburn, Constitutional Law professor at the South Texas College of Law and an adjunct scholar at the conservative Cato Institute, further argues that “for well over a century all three branches of government have relied on a shared understanding of this provision [of birthright citizenship.] People born in the US are citizens, regardless of the citizenship of their parents. As executive order by President Trump cannot erase the original meaning of the Constitution . . . The legal arguments against birthright citizenship are inconsistent—not only with the 14th Amendment, but with over a century of practice, in which all governmental branches have recognized the children of foreign nationals as citizens. More than 150 years after the amendment’s ratification, this ‘gloss’ on the Constitution cannot be trumped by disputed definitions of ‘jurisdiction,’ or with outlier statements (sometimes misconstrued) during the ratification debates. Birthright citizenship is correct as an original matter and has been reinforced by widespread agreement within the republic.”

It is therefore quite clear that the original meaning of the 14th Amendment is birthright citizenship. If the president of the United States wants to change this, there is only one way to do so—by proposing a constitutional amendment. There is no other way to change this well-documented understanding of the 14th Amendment. As the Wall Street Journal editorialized, “[President Trump] undermines his legal standing, and his political credibility, when he pulls a stunt like single-handedly trying to re-write the Fourteenth Amendment.”

See Jill Lepore, These Truths, pp. 311-330; Wall Street Journal editorial (31 October 2018); Josh Blackman, “Birthright Citizenship is a Constitutional Mandate,” in the Wall Street Journal (2 November 2018); and Adam Liptak in the New York Times (31 October 2018)