Are Human Rights Anchored In Natural Law Or Positive Law?

Sep 1st, 2018 | By Dr. Jim Eckman | Category: Culture & Wordview, Featured Issues, Politics & Current Events

In June, the United States withdrew from the United Nations Human Rights Council, which UN Ambassador Nikki Haley described as “a protector of human-rights abusers, and a cesspool of political bias.” This UN Council is quite frankly a sham. Aaron Rhodes, author of The Debasement of Human Rights: How Politics Sabotage the Ideal of Freedom, writes that “The Human Rights Council has become a cover for dictatorships. They assume the high moral ground of standing for ‘dialogue’ and ‘cooperation,’ a tactic for smothering the truth about denying freedom. Raising human-rights concerns is dismissed as divisive and confrontational, and a threat to ‘stability.’ Most of the debate there is technocratic blah-blah about global social policy—not about human rights at all.” Rhodes argues that a major philosophical error has emerged in the modern understanding of human rights. That error is the merging of “natural law” with “positive law.” Rhodes argues that “positive law” is the “law of the states and governments.” A statue such as the Social Security Act of 1935 creates “positive rights”—government conferred rights to which citizens have a legal entitlement. In 1944 Franklin Roosevelt exhorted Congress to enact a “Second Bill of Rights,” all “positive” rights—including the rights to “a useful and remunerative job,” a “decent home,” “adequate medical care” and “a good education.” The growing emphasis on what Rhodes calls “positive rights” has led to these developments:

- “The European Union, and its Charter of Fundamental Rights, says that the right to have free employment counseling is a human right.” That “equates something as banal as employment counseling like the right to be free from torture, or the right to be free from slavery.”

- The UN Human Rights Council is under the influence of Islamic theocracies and China, so that these nations are “forming a human-rights vision of their own; Human-rights without freedom. Its human rights based on economic and social rights, where freedoms are restricted in the interest of ‘peace’ and ‘stability and power’—their power.”

- All of this has “installed a kind of passivity among people” living in unfree countries. They expect that “they can fix their society through human rights. But the human-rights system is impotent; it doesn’t have any teeth. There’s an illusion that the UN is going to force my government to protect me. No it doesn’t do that. So civil society puts all of its energies into this structure, which can’t do anything.”

- The 1975 Helsinki Accords offered some hope that the UN would adopt a semblance of natural rights. The Soviet bloc joined the West in pledging to “respect human rights and fundamental freedoms including the freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief.” But tragically, no one really paid attention to these Accords.

- The 1982 Vienna Declaration did concern itself with natural rights but primarily it stressed the familiar positive ones such as policing private conduct and attitudes and crimes such as domestic assaults, sexual harassment and “social and psychological barriers that exclude disabled from full participation in society.”

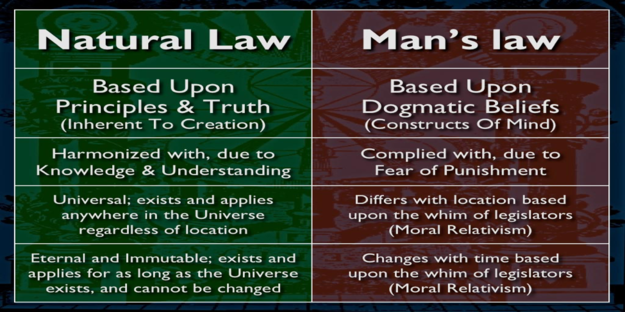

What is the difference between “positive law” (and rights) and “natural law” (and rights)? Most philosophers and theologians regard natural law as a body of unchanging moral principles regarded as a basis for all human conduct; it is a philosophy asserting that certain rights are inherent, innate to human nature, endowed—traditionally by God or a transcendent source—and that these can be understood universally through human reason. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) saw morality stemming from natural law as a function of the rational human nature that God has given us. Natural law produced a universal set of moral and ethical principles by which humans are to live.

The Founders of the American Republic agreed with the principles of natural law, which then produced an adherence to natural rights. The Declaration of Independence of the United States saw life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness as natural rights “endowed by their Creator.” Those natural rights were then further itemized and guaranteed in the Bill of Rights, the first Ten Amendments to the US Constitution.

As a Christian, I believe we can make the case for natural law and natural rights. Here is a chart that summarizes the difference between natural law and human law, which is not rooted in universal principles, such as the revelation of God in Scripture:

As Aaron Rhodes has argued, a civilization based solely on what he calls “positive law” has produced an understanding of law and rights that is not only indefensible, but is actually ludicrous and harmful. The UN Human Rights Council demonstrates this folly perfectly.

See James Taranto on Aaron Rhodes and his book in the Wall Street Journal (18-19 August 2018).